Segovia Scales Part 3 - The G scale

Embracing the smaller patterns within the larger three-octave scales

In many countries, the pitch G is referred to as Sol. I personally associate the key of G with a bright, brassy quality—the name sol feels solar to me. When I think of G major, I think of the sun.

This third essay on Segovia’s scale patterns focuses on the scale pattern that he initially presents as a G-major scale.

This series on the Segovia scales is intended to be comprehensive so that each essay is about one of his scale patterns and can serve as a self-contained resource for smaller scale patterns as well as strategies for how to move from position to position with “fretboard awareness.”

I predict that when I am done with the series, I will be inclined to write more focused exercises for becoming more fluent with a certain pattern. If you find any of these essays overwhelming, keep in mind “it’s not you, it’s me.” I am writing about the scales this way, because I want to organize them this way in my head. It might not work for you, but hopefully, you find something useful. If one observation in one essay changes your approach to the fretboard on a given day, then mission accomplished.

I like the idea of having observations about a single Segovia scale pattern in one place even if the usefulness of the observation cannot be fully absorbed in a reading. In the spirit of establishing a DIY guitar practice, this approach allows us to use one particular observation as a springboard for inventing an exercise, as a “ways of seeing” the fretboard.

The scale fragments I find in Segovia’s scales suggest paths through the fretboard. They reveal new things to me despite the fact that (as in frequent moments of self-criticism) I think I “should” already know all this after fifty years of guitar playing. Nevertheless, I’ve never seen or heard anyone analyze these scales quite this way.

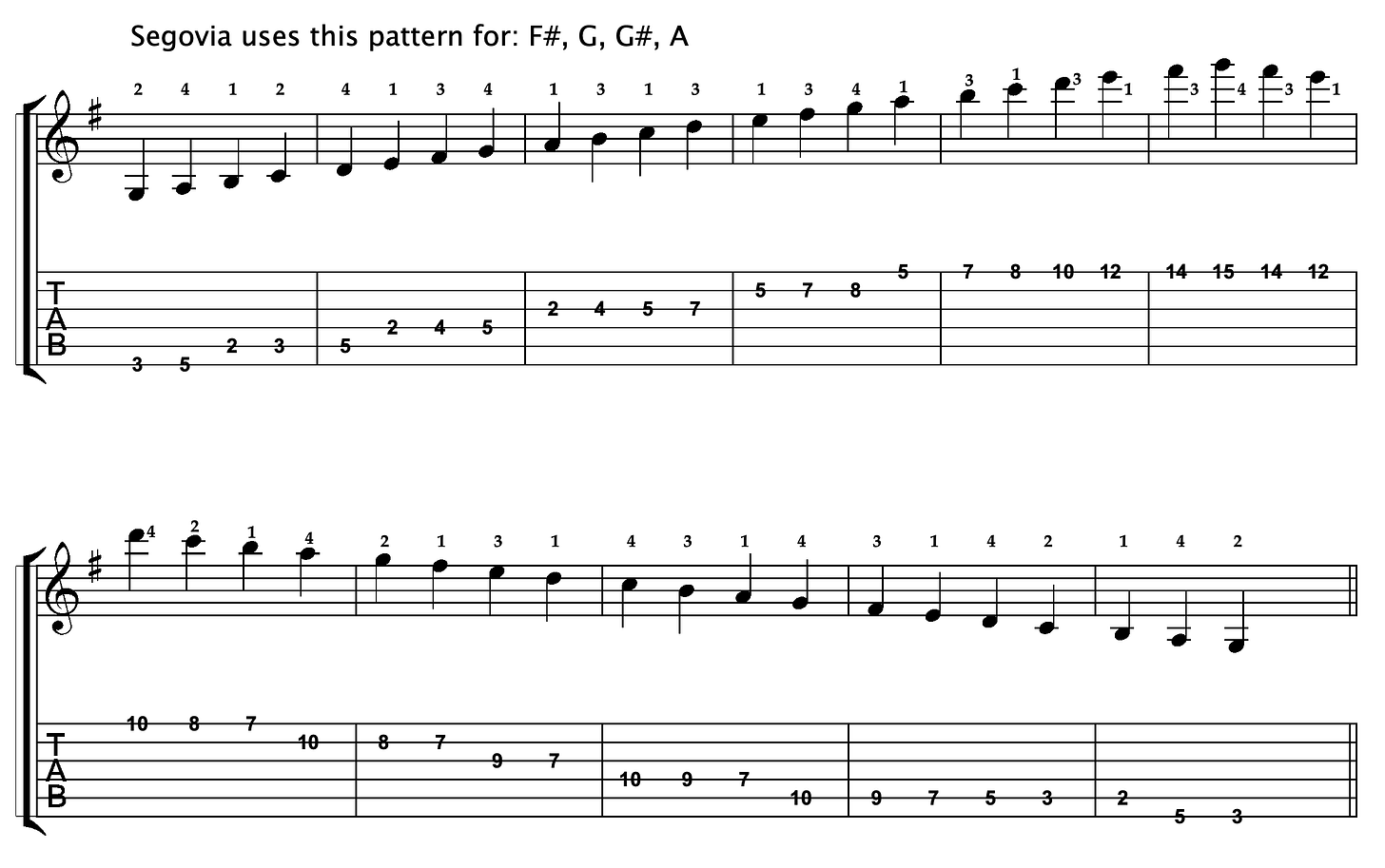

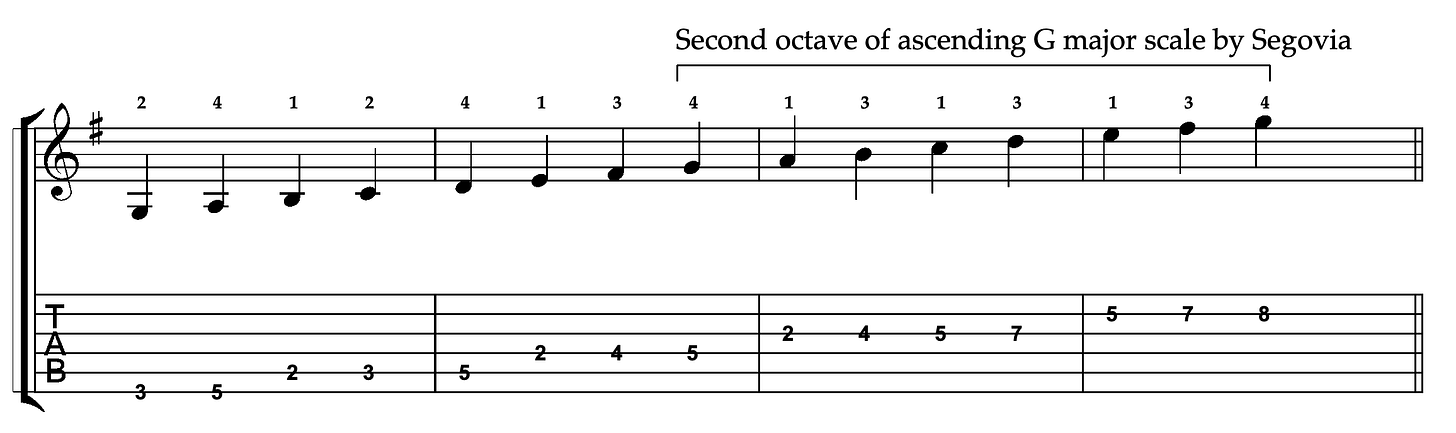

I will begin with the pattern as Segovia presents it.

If you have learned this scale before, review it. If you haven’t, come back to it later after it has been broken down into fragments to be studied on their own. The first of these fragments has characteristics similar to the scale presented in the first essay.

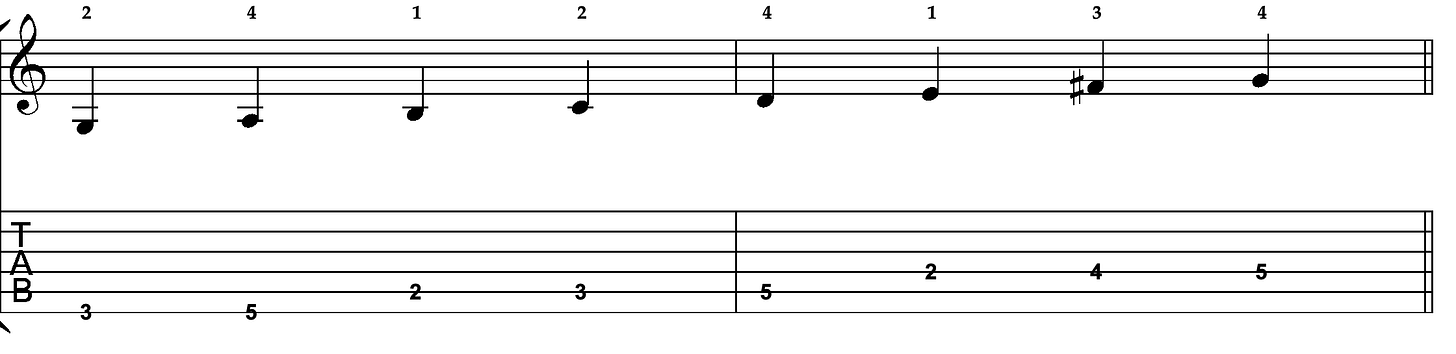

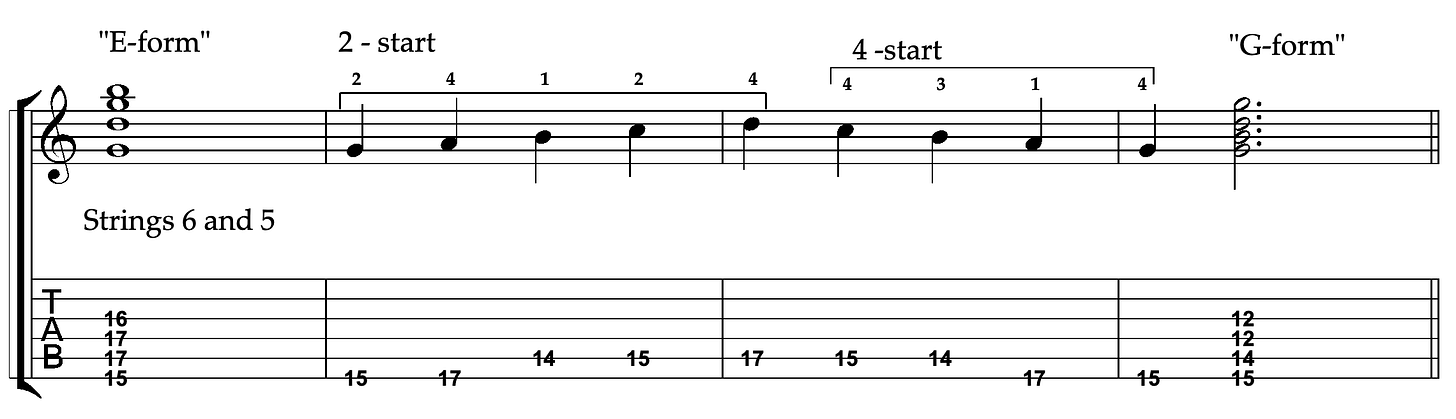

This is a one-octave G major scale that uses two of the major tetrachord patterns discussed in the first essay of the series. The scale begins with 2-start major tetrachord on string 6 (pitches G, A, B, C) and the second is a 4-start major tetrachord starting on string 5 (D, E, F#, G). I think of this scale as the major scale that belongs with “E-form” of the CAGED system.

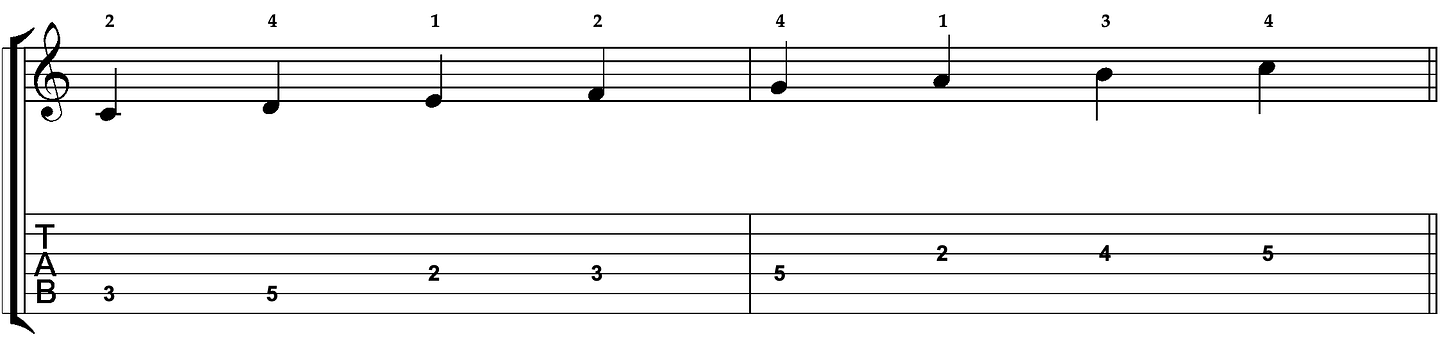

Typically, that chord form in the key of G is imagined as a bar chord in third position. The scale is in second position. It’s a good idea to build a strong mental association between this scale pattern and the “E-form” chord shape. If we shift the pattern to strings 5 and 4, we get the C major scale discussed in the first essay.

The scale pattern when it starts on string 5 should be associated with the “A-form” chord shape (a barred C major chord in position 3).

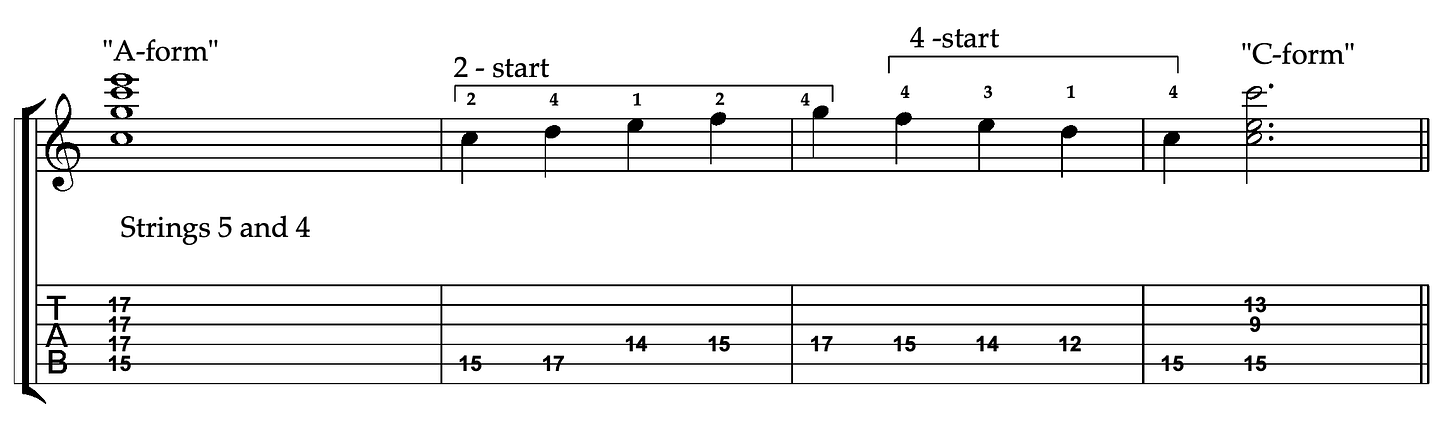

Let’s stay with the idea of linking scale fragments with chord forms in C major for a moment.

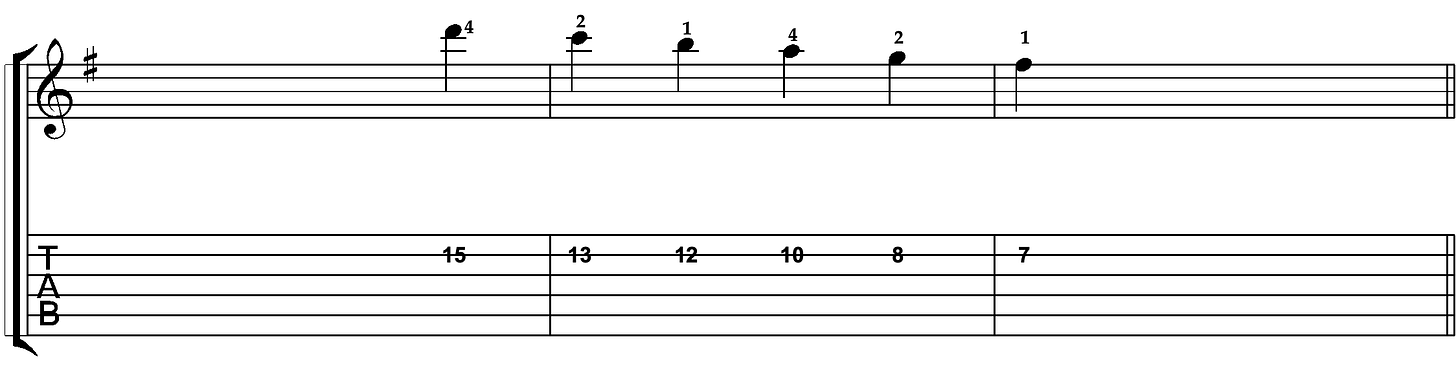

In the key of C, the above exercise begins with a C major chord using the “A-form” in position 15 (an octave above the familiar position 3 version). The exercise ends with a C major chord (omitting the chordal fifth) using the “C-form” in position 13 (an octave above an open C chord).

The scale begins with the 2-start tetrachord and shifts on finger 4 to descend using the 4-start tetrachord.

To summarize: if finger 2 on string 5 is in a scale or melody and on the root of a major chord, it’s an “A-form” chord. If finger 4 string 5 is on the root, it’s a “C-form” chord. I suggest taking some time meditating on these associations.

Here are the corresponding patterns on strings 6 and 5. Notice we have made links between major tetrachords and almost all of the chord forms in the CAGED system.

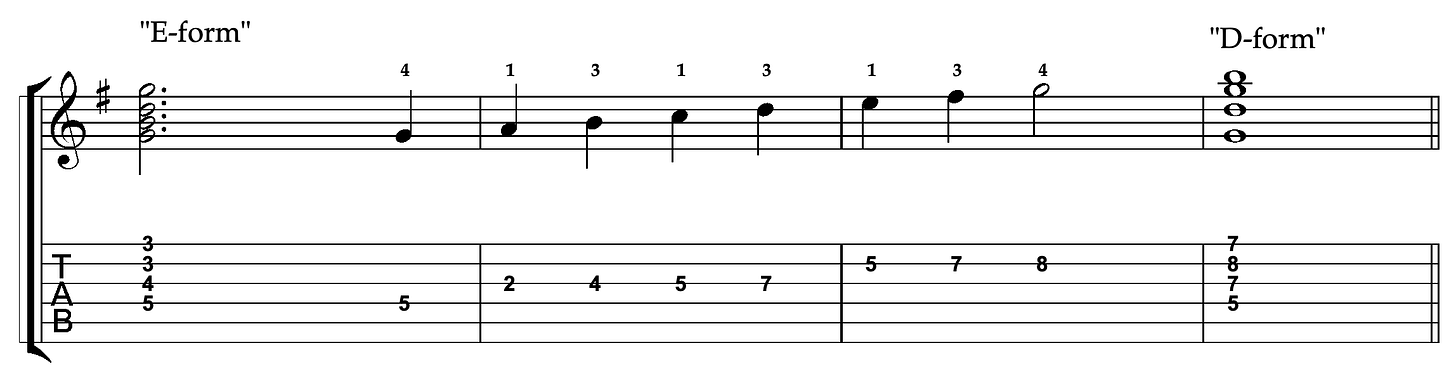

What’s missing? The “D” form. We’ll see it in the Segovia pattern discussed in this essay.

On string 4, a 4-start major tetrachord links with the “E-form” and on string 2, it links with a “D-form.”

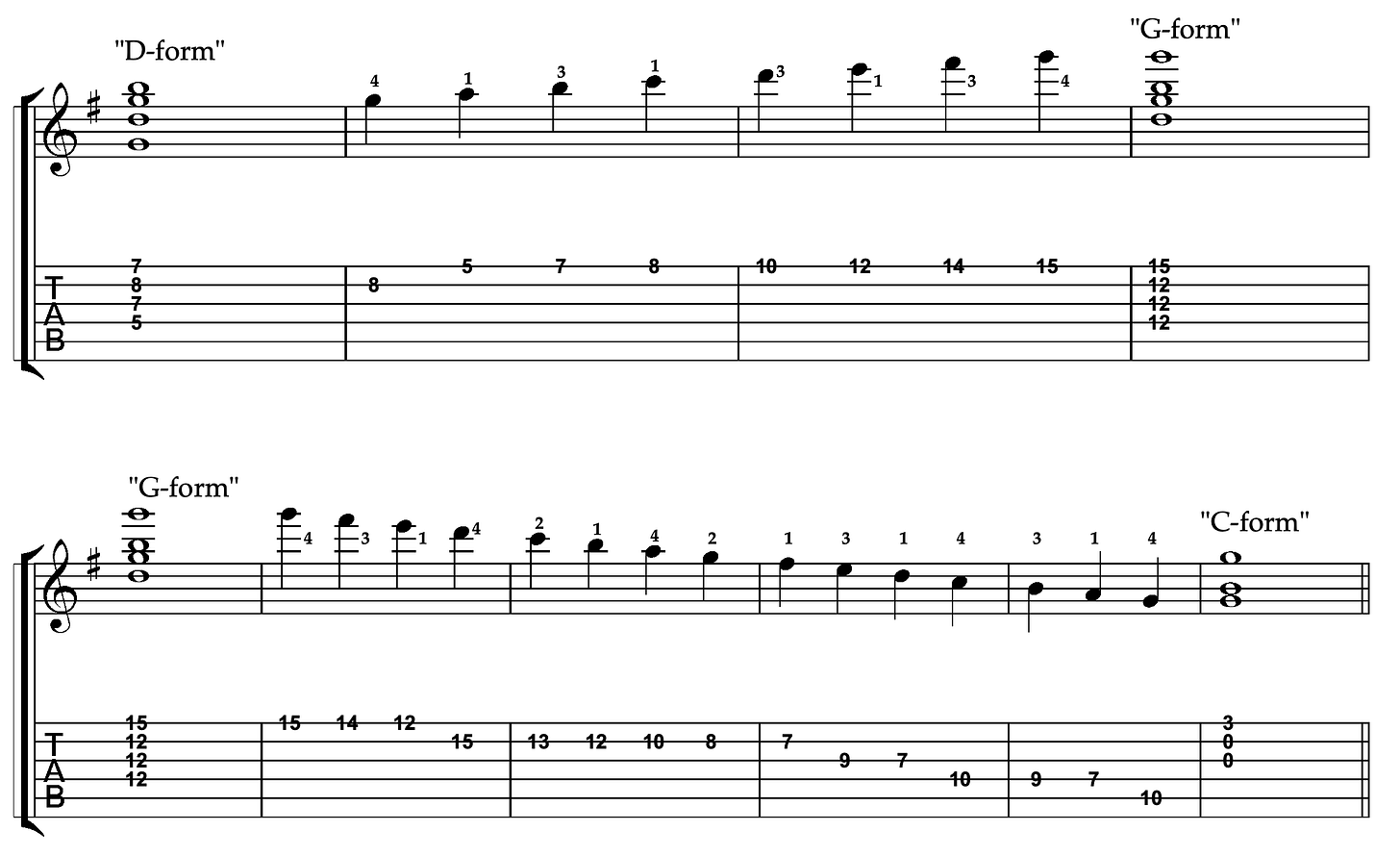

One of the interesting features of the overall pattern of the original scale which began this essay is that Segovia ascends the three-octave scale one way and descends another. This is also the case with the A minor scale discussed in the second essay, but that scale is melodic minor and the second tetrachord is a different palette of notes. It’s less surprising that the fingering would be different descending. But why does Segovia provide a fingering variation for descending the G major pattern?

I believe that he sees a logic in both versions based how the scale fragments relate to the chord-form shapes. The ascending version connects the “D-form” position with the “G-form” position. The descending connects the “G-form” position with the “C-form” position.

Both versions should be practiced ascending and descending. I do not believe there is a practical advantage for ascending one way and descending another. I believe it’s a case of Segovia wanting to practice both versions.

In a future post, I may address the “horizontal” patterns more. It isn’t hard to find the shifting minor tetrachord used in several places in original Segovia G-major pattern. There’s also a pattern that shifts along string 2, which we might call a “locrian” pattern, but I will explore it in more detail another time.